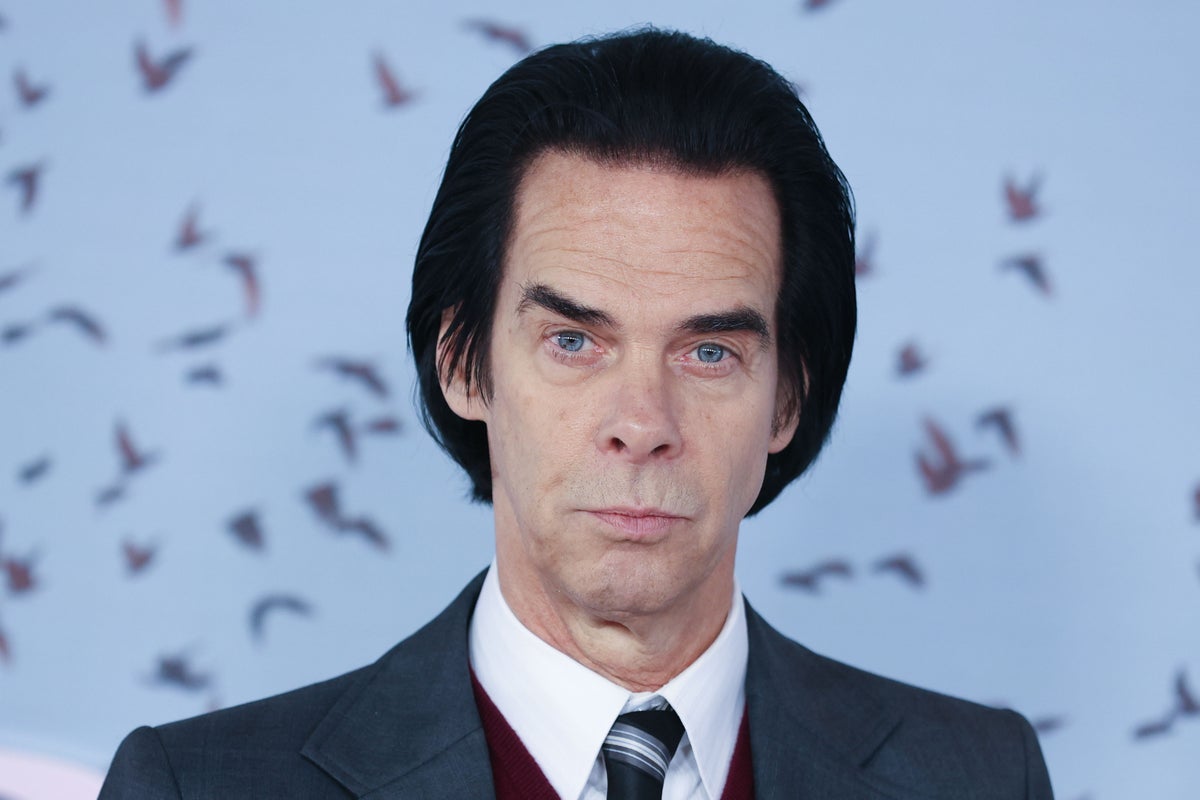

Nick Cave’s Veiled World documentary is a captivating look at his songwriting genius

In Nick’s world, there are always characters, people, songs, him… dealing with the unknown.” For decades, Nick Cave has been more than a mirror of the things we’re afraid to confront. He’s a conduit, a doorway into a different dimension that bristles with outlaws, ghosts, murderers, thieves, scorned lovers and tortured souls. Sky’s new documentary, Nick Cave’s Veiled Worldgoes some way to lifting that veil and delivering a fascinating, insightful portrait of the Australian artist’s creative process.

“Another music documentary?” you might well sigh, and rightfully so. We’re stuffed to the brim, Christmas turkey-style, with endless and often hastily thrown-together projects promising “the most in-depth” of looks at our favourite artists, or indeed our most controversial. The problem with many of them is their endeavour to present the whole picture, too often with broad brush strokes and leaving viewers with the feeling that, actually, they haven’t learnt anything new.

Not so the case with Veiled Worldwhich homes in on Cave’s songwriting process – how he conjures up these dark, mysterious worlds, and what drives him to do so in the first place. It helps that Emmy-nominated director Mike Christie has assembled some of the musician’s closest friends, collaborators and admirers – Warren Ellis, Florence Welch, Colin Greenwood – to offer their own thoughts on his work and why we’re so drawn to it.

The documentary is divided into chapters, opening with “The Outlaw”, which examines the characters Cave has introduced us to. As Red Hot Chili Peppers’ bassist Flea points out, his songs are “full of the most divine, beautiful characters. And then, you know, there’s the most pathetic of victims, the most ruthless of evil-doers, and just the worst of humanity.” Men like the narrator in “The Mercy Seat”, from Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds’ 1988 album Tender Preyare not necessarily ones you’d want to find next to you at the bar.

But, as Scottish author Irvine Welsh puts it: “The great thing about anti-heroes is they give us permission to transgress without actually transgressing.” Cave, as the documentary deftly lays out, has a unique way of positioning himself in some truly troubling perspectives: the man on Death Row in “The Mercy Seat”, for instance, or the killer in “Stagger Lee”. In the case of the latter, filmmaker and Cave collaborator Andrew Dominik recalls attending one of Cave’s early performances of the song, which follows with graphic detail the exploits of its foul-mouthed murderer. “You could feel the absolute shock… there’s 50,000 people that just felt like they’d been slapped,” he says.

By the second chapter (“The Shadow”), we’re already presented with evidence of how Cave’s songwriting and ideas just keep evolving. It touches on his past issues with heroin addiction, respectfully, to note how he had feared that without drugs he would not be able to plumb those same depths. Obviously, his concerns were misguided; just listen to 2004’s Abattoir Blues/The Lyre of Orpheusor 2016’s Skeleton Treereleased not long after the death of Cave’s teenage son, Arthur.

One of the most moving scenes comes from longtime Bad Seed member Thomas Wydler, who recalls hearing that Arthur had died in a fall near the family home in Brighton. “The worst thing,” he answers, wiping tears from his eyes. “It was the worst thing I’ve ever heard. And I’ve never forgotten it.”

How did it affect Cave, not just as a man, but as an artist? “That kind of grief is a form of madness,” says Seán O’Hagan, the Irish journalist and critic with whom Cave co-wrote the 2022 book Faith, Hope and Carnage. “It brings you pretty close to going under.”

Cave’s stance on art had already shifted by this point: “For most of my life, I was sort of just in awe of my own genius,” he says in a voiceover excerpt from an ABC interview, with a self-deprecating snort. “I had an office, and I would sit there and write every day… whatever else happened in my life was peripheral, even annoyances, because I was involved in this ‘great work’.

“And this just collapsed completely, and I saw the folly of that, the disgraceful self-indulgence of the whole thing. My priorities changed… that idea that art trounces everything, it just doesn’t apply to me any more. I’m a father, and I’m a husband, and a person of the world. These things are much more important to me than the concept of being an artist.”

Perhaps with this shift, though, Cave has managed to unlock something even greater, a connection to unknown forces that enabled him to make as remarkable and devastating a record as 2019’s Ghosteenwhich to Ellis felt like “the only time I’ve been in the studio, where it felt like something else was in there – another force was present in there”. Veiled World is by no means the “full picture” of Cave. But it is a captivating, lovingly created film about the genius of one of our greatest living storytellers.

‘Nick Cave’s Veiled World’ airs tonight (6 December) at 9pm on Sky Documentaries

Post Comment