We explain the biggest changes between the film and the book

Guillermo del Toro has always had a soft spot for monsters. But no one expected his version of Frankenstein, now available on Netflix, to be so emotional and personal.

The result? An adaptation that honors Mary Shelley without being bound by the chains of literal fidelity. And that’s where the fascination lies.

A classic redesigned with soul

Every horror fan knows the image of Frankenstein created by cinema, the monster with slow steps, an empty look and an innocent heart. But anyone who has read Mary Shelley’s book knows: the original Creature is articulate, tragic and painfully human. Del Toro decides to unite these two worlds.

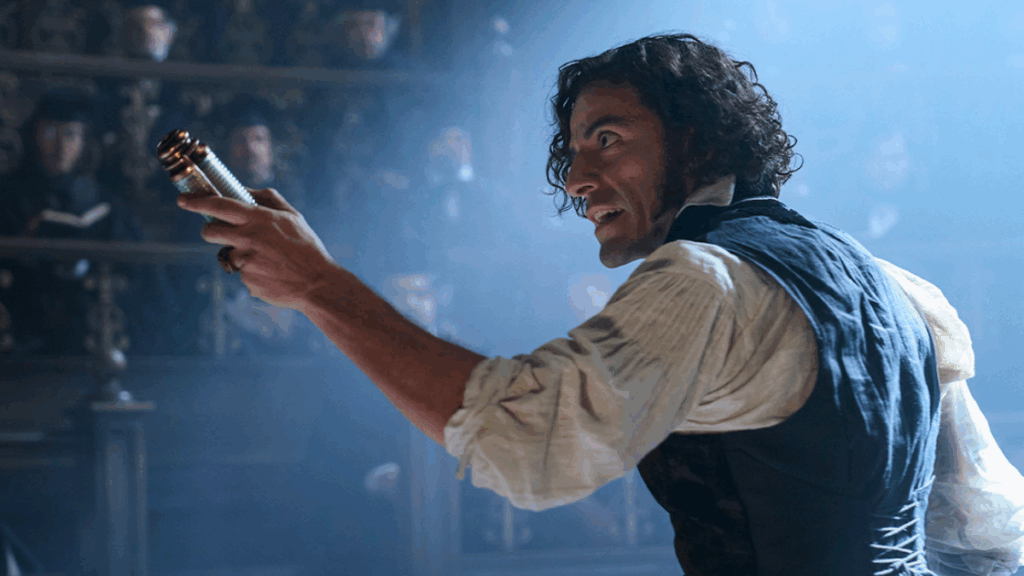

His film maintains the essence of the novel, the obsessed scientist and the creature who wants to be loved, but changes the point of view. Here, the film is divided between the account of Victor Frankenstein (Oscar Isaac) and that of the Creature (Jacob Elordi). It’s as if the director said: “they both have wounds that deserve to be heard.”

And that changes everything. After all, the true horror has never been the monster, but the mirror it offers to its creator. Del Toro understands this better than anyone, and turns the myth into a dialogue about guilt, rejection and forgiveness.

The structure Shelley started, Del Toro completed

Mary Shelley used a layered narrative: a captain listens to Victor’s story, who in turn narrates the pain of his creation. Del Toro updates this structure, letting the Creature take control of the story. It’s as if, finally, the monster gained its own voice.

The change of narrator is not a mere technical detail. It is a gesture of empathy, the same thing that the scientist lacked in his arrogance. The result is a work that breathes like something new, even carrying echoes of 1818. And who knew that a story from two centuries ago would still seem so current?

Furthermore, the film takes place in the 1850s, in the midst of the Crimean War, which gives the drama a more cruel and realistic context. While bodies are used in war, Victor uses corpses to defy God. Coincidence? Nothing in Frankenstein is.

The creator who became a monster

In other versions, Victor Frankenstein is just a dreamer who went too far. Here, he is something darker and more human. Del Toro transforms the scientist into a man marked by an abusive father (Charles Dance) and the death of his mother. The monster is actually born long before the experience.

When the Creature comes to life, Victor calls him “son”. But love soon turns to hate. Frustration takes the place of fascination, and the scientist repeats the violence he suffered. It’s a cycle of abuse, and the film shows it with an almost unbearable sadness.

Unlike the book, where Victor runs away terrified, here he tries to kill his creation by burning down his own laboratory. A powerful inversion: the father trying to destroy his son, the man erasing his own humanity. Del Toro, once again, prefers drama to morality.

Elizabeth finally has a voice

In Shelley’s Frankenstein, Elizabeth (Mia Goth) is sweet, obedient, almost a decorative figure. In Del Toro’s Frankenstein, she is flesh, thought and soul, played with strength by Mia Goth. This time, she is not engaged to Victor, but to his brother, William.

This change is crucial. Elizabeth is no longer the passive victim, but a curious woman, who loves science and questions the world. She is the counterpoint to Victor’s ego: she seeks to understand life, not control it. When he crosses the path of the Creature, the bond between them is pure, almost maternal.

There is something poetic about this. The woman that everyone treats as an object is the one who sees humanity in the being that the creator despised. It’s Shelley rewritten by a man who actually read Shelley and understood her heart.

A new kind of tragedy

In the original story, the Creature’s hatred leads to the death of everyone Victor loves. In the film, the cycle is broken. Violence exists, but the outcome is different: there is guilt, there is loss, but there is also forgiveness. Victor, in his last moments, apologizes to his “son”.

The Creature, in turn, accepts. He no longer wants revenge, he just wants to exist. It’s a scene that echoes an alternative ending to the entire history of modern horror: the monster, finally, finding peace.

Frankenstein is reborn

“Every artist portrays himself in his work,” Del Toro once wrote. And Frankenstein is the author in front of the mirror. The director sees in Victor the creator who lost control of his own creation and in the Creature, the sensitive and rejected being who just wanted to be understood.

Unlike versions that only imitate the book, this one breathes creativity. The photography, inspired by Victorian painting and candlelight, gives the film an almost spiritual aura. The result is a rare blend of gothic horror and visual poetry, something only Del Toro could create.

Perhaps the greatest compliment is this: after so many versions, the Frankenstein myth seems alive again. And, ironically, it was the filmmaker most passionate about monsters who gave him back his soul.

Frankenstein is available on Netflix.

The post Frankenstein: We explain the biggest changes between the film and the book appeared first on Observatório do Cinema.

Post Comment